The Billy Faier Collection

(Image is from Billy's October, 2007 visit to Saint Paul)

Ok, right off the bat, it might as well be admitted that Billy Faier is a musical hero around here, and that status predates the founding of the Archive Project by nearly 40 years. The lack of recognition by the listening public of his contributions to American music is unfathomable, but if you want to elicit an "Oh, my word yes..." reaction from careful students of our musical heritage, just mention his name.

There have not been a flood of recordings from the man whom a lot of folks would simply label "the best all-around banjo player to ever travel the old roads of the American Nation." Every ten years or so there would be an album. The knowledgeable would stumble over it at the Electric Fetus or a similar music store somewhere else in the country, and clutch it to their chest, throw money at the cashier and write off the rest of the day.

Yes. He's that good. Yes, he's still that good at 76 years of age.

Don't get this wrong. Banjo players are a particular kind of icon around here. And there are really good arguments that Scruggs is better at what Scruggs does... or Bella Fleck or Dick Weissman or Eric Weissberg or Erik Darling or Peter Seeger. But Billy Faier has simply never recognized that there are any limits to what can be done on an instrument that some call "primitive." In the 1950s he took a year and figured out how to transpose an old-time fiddle tune called "The Last of Callahan" to the five-string and then delivered it flawlessly on his first recording, The Art of the Five-String Banjo, in 1957. He has done the same with music from sources as varied as a traditional tune heard once on a radio in a bus in South America, Elizabethan love songs, classical music and his own compositions capturing the landscape of America and the longings we all share. Who else plays Bach on the banjo? Who else has figured out how to simultaneously and seamlessly play it as a stringed and percussion instrument? And who else has his other credentials?

We'll go along with best all-around...

Ramblin' Jack Elliot has a song/story called "912 Greens," built around a quest to search out "a legendary five-string banjo player" in New Orleans. It's set in 1953. The five-string legend is Billy Faier. And Jack's ascription of status as a legend to him was at a time four years before his first album.

Billy's solo albums are listed below. What is not listed are the innumerable compilations of banjo artists upon which his work has appeared. There is also a link to his website, where signed CD copies of the albums can be purchased directly.

It has been over 20 years since he recorded a new album. He's been plenty busy, but those are stories for another time. We're working on it...

For now? There's a recording of a house concert he gave on October 13, 2007, on a visit to the Archive Project to talk about the history of American folk music.

It's labeled as a bootleg. And that's accurate as far as it goes. It was recorded with his permission, from the audience, in a very intimate setting. There was no discrete microphone for his vocals and there are a couple of people kicking themselves around Saint Paul, Minnesota, because of that fact and the result that his voice could use a little bit higher level on a couple of the songs. The good news is that the microphones used were very good, and his banjo playing is captured with all its brilliance and timbre. The recording is, literally, like being a member of that small audience and sharing the experience with the folks from four to sixty-something who were captured by, and with, a 76-year-old American musical genius.

It was not recorded with any intention of general release. There had been some expression of interest in bringing him in for performances at venues in Minnesota and Wisconsin. We wanted to have some material to play in response to those inquiries--to show just how good the man's chops still are. But when it was heard, it shouted to be shared with those who know his name, those who might have missed him, and some new generations who are only now learning about our common musical heritage.

Billy's newest fan will be five years old in the Spring of 2008. She gets it.

So can you.

What follows

are some thoughts about the album, the artist and the music, or you can click here

to jump down to the samples or here to look at or order

Billy's earlier albums.

Billy Faier Live 2007

The Downstairs Concert Bootleg

Produced by Northern Plains Archive Recordings, Ltd.

Image is from the front cover of the CD insert

(Photograph by Angela Henriksen)

32 Tracks, 16 songs, 73.5 minutes total

Spend a little time with Billy Faier and you will realize you have come into contact with the essence of something unique to the music of America. He's the pure stuff--basic, real and unalloyed--but he's not an echo of our heritage of song. It's much more like having that inheritance itself sit down at your table and break bread with you.

He's not just carrying the sounds of an older time, and his own additions to the genre. Those songs, from the places and people we were once and may still be, find increase as they pass through him to his audiences. The banjo style is entirely his--dense and yet amazingly clean--complete and unique. Songs are not just played on that old five-string, they are performed, in the best sense. You can lose yourself in them and begin to wonder just where all that richness is coming from, because surely it cannot all be produced by just five strings and two hands...

The experience is darn near bardic. Along with the music come stories, lessons and history. Unlikely as it seems (once you've heard him play and sing) the context he carries like a glow around himself and offers to others may be richer than the music itself. After he left Saint Paul, he went back out on those old western roads, listening to the land and carrying the lore. He was asked to deliver two lectures to high school audiences in Marin County, and wound up honoring an on-the-spot invitation for a third, long session just with the school orchestra. That's a heck of a day for anyone. Among other things, it tells us our enthusiasms are hardly misplaced.

This is a good point for you to sample his music for yourself. Track listings for albums on these pages normally appear after the discussion, but this time they are being offered with 30-second samples from this new album. Before turning to the long essay Billy and the session deserve, particularly if you are only just catching up to this American Master, feel free to taste the songs he gave us on a Saturday night.

Track Listing (Click buttons for 30-second low-resolution samples of the songs)

1 Opening

and intro

2 "The Great Assembly" ![]()

3 Outro/Intro

4 "Song of The Grand Canyon

Mule Driver"

![]()

5 Intro

6 "Cluck Old Hen"

![]()

7 Intro

8 "Song of the Cuckoo"

![]()

9 Outro/Intro

10 "Bright Angel Rag"

![]()

11 Intro

12 "Five-String Fanfare"

![]()

13 Intro

14 "Zzyxx" and Break Announcement ![]()

15 Post-Break Intro

16 "Together Free"

![]()

17 Intro

18 "Dog's Life"

![]()

19 Intro

20 "Live and Let Live"

![]()

21 Intro

22 "It Was a Lover and His Lass"

![]()

23 Outro/Intro

24 "South American Tune"

![]()

25 Outro/Intro

26 "Whoa Mule"

![]()

27 Intro

28 "Miner's Lifeguard"

![]()

29 Intro

30 "Folk Singer's Heaven"

![]()

31 Encore Call

32 "Little Maggie" and Closing

![]()

**

(Click

here to skip to price and ordering information.)**

The live session proves that Billy is still, very much, on his game. In a way it's a celebration of the 50th anniversary of the release of his first album, back in 1957. Mostly, it's a celebration of American music and his unique contributions to our common musical heritage.

It's also a terrific story, and that tale is all wound up in the history of American "folk" music, and Billy Faier's role as an observer, participant, journalist, picker and, sometimes, juggler. The image at the right from the back of the CD is part of the story in the insert.

Cue the essay...

There are a ton of definitions for that term--"folk"--let alone the long-tons of the same that have been applied to "American folk music." Some of the more interesting of the resulting epistemic and philosophical differences and controversies (for folk music loves a good controversy) turn around one point in time--June, 1958. That was the date of release of the Kingston Trio's first album and the resulting explosion of folk and folk-tributary songs onto the Billboard charts after "Tom Dooley" went Number One that November. Oh, you can argue that it all goes back, instead, to the Weavers, and the popularity of Huddie Ledbetter's "Goodnight Irene" in the summer of 1950. It's a pretty darn good argument, actually. "Irene" was very like a signpost to the future, when songs and themes that had been carried from memory to memory, from porch to shivaree to prison and back, that had somehow welled up out of the common folk of the nation, were set into "popular" arrangements and sold in our marketplaces. Don't forget that it was the Gordon Jenkins' arrangement and orchestration that propelled the Weavers onto the sales racks.

But it was a long time between the summer of 1950 and the summer of 1958, and in a number of ways "Tom Dooley" is a better marking point in time for discussions like this. The song, and its commercial success, offer a clear delineation between "traditional" American folk music (whatever that means) and "modern" or Popular Folk. That demarcation offers a pathway into the hidden history of the nation, for those who are so inclined. And Billy Faier doesn't just look a little like one of those old-time scouts, he is one, and has been the same sort of guide to the beauty of the hidden places in our music and the gentle truths of his own writing. Ok, he's also capable of more than a little whimsy and some sly entendres of a multiple sort, but then so's our real music, friends.

And he was there, on both sides of the divide we're talking about. His first two albums, Art of the Five-String Banjo and Travelin' Man, date from 1957 and early 1958, and he recorded albums in the sixties, seventies and eighties. He published a magazine about the music when he wasn't traveling, sometimes with a carnival, juggling and doing amazing things with a banjo and guitar. Perhaps, if he had been a little more keen for the spotlight... But that's not really been his style. Some of us found him in the sixties by backtracking from the records of the first Newport Folk Festival, in 1959. We heard some really outstanding accompaniment on those, but the guy never took the microphone. Some of us ran his records down after we encountered the soundtrack from In White America and were taken by the spare and elegant music he provided between those shattering and illuminating historical narratives from the actors. And some of us have moved those records a lot of times, packing them in that special box that went in the car with us, when the rest were just shipped.

He has helped us personally, as well, in our on-going search for the sound track to the hidden history of the nation and the role of that 1958 watershed (and some others), and that deserves some talking here. But first we need to think about powwows and the songs sung at them, because they offer a clear and contemporary example and preservation of something very basic to American music.

And yes, that does, indeed, have a direct relation to the story...

A "wacipi" or powwow is a social gathering of the people of the First Nations on this dirt, open to all of us. If you haven't attended one, it is sufficient to say that the dancers are supported by human circles of singers, gathered around drums. There's a whole lot more than that going on, but this is not the place, beyond noting that oral and community histories are thick in the air and in the group consciousness that emerges, unique to each gathering. The songs that are sung are rarely written down, but they are very much part of that collective, unwritten history. And they are not copyrighted, in the sense of being registered with the US Copyright Office. But they belong to someone, most often to a family lineage that reaches back, far into the generational past. A drum group must be given permission by the family before one of those songs can be performed. If another group were to appropriate a song without permission, it is guaranteed that it would get very, very quiet in the place. REALLY quiet...

Maybe it's something in this old dirt, or the breathing of the air, or the crying of the rain crows (American Yellow-Billed Cuckoos), but something quite similar happened in certain areas of the country among the immigrant population that had originated in Europe and drifted down the Piedmont marked by the Appalachians and the Atlantic, and into future states bordered by the Gulf of Mexico. Certain families kept history in song, times and happenings preserved in the amber of voices and instruments. And those songs were passed along down their generations right along with the oral family history, the family bible, grandpa's musket, and certain recollections of embarrassing events. They were, after all, families.

It's also true that a lot of our music came across the Atlantic in the heads of those who were brought against their will, those whose options were limited by indenture or language, and those who were either running away from something or toward something on a personal level, (as has been said elsewhere) as well as some people who traveled first-class. Then it was passed through the filters and hard ways of life in a different place and sometimes it became something distinctive to the American setting, perhaps as a tune under new lyrics or verses combined from different pieces.

But some of the songs preserved in those hills and plains and hollows and sung in parlors and dockside taverns were entirely original to this place. They spoke to things that had happened, or might happen, and the lessons found in lives smaller than those of lords and ladies, (some of them named Randall). It has been said that "Springfield Mountain" is the very first American folk song, with its story of mowing hay, love proven, a disastrously placed snake and the death of two young people. It could be the first, but it's never been a big favorite around here. Then Billy Faier came up to talk about folk music and sang a version that just plain jumped. Anyway...

All this leads us back to "Tom Dooley," and the seam that opened up in our music. In 1938, Billy was coming up on his eighth birthday, living in New York, nine years from picking up the banjo. Well to the south, in North Carolina, another New Yorker named Frank Warner was visiting a friend and fellow preserver of music that wasn't written down. The Carolinian's name was Frank Proffitt. The Proffitt family, and Frank in particular, had been one of those that had gathered and preserved songs for years, with Frank's father Wiley and his aunt Nancy Prather contributing many of them, and others gathered from friends and neighbors over that time. As time went on, Proffitt would share more than a hundred of those songs with Warner. One of those he passed on in 1938 was a ballad called "Tom Dooley."

And then ten or twelve years passed, with the dislocations and trauma of World War II, and a lot of things changed, like disposable income and demographic patterns. Burl Ives' first folk music radio program had been broadcast on the day Paris fell. Soldiers took swing to war and came home to bebop. The first "baby boomer" was born. Colleges absorbed the surge of GI Bill students in classrooms and married housing facilities...

By the late 1940s and early 1950s, Billy and his banjo and, by totally separate trajectory, that ballad, had all found their way to New York City's Greenwich Village. There has to be a story in the song's journey in those 10 years or so after it left North Carolina, but it hasn't yet been discovered here. And we're not real sure what Alan Lomax's role was either, other than publishing it, but he, Warner and Proffitt are all credited on Proffitt's recording of the song for Folk-Legacy in the early 1960s. That's another of the ones we're working on...

Billy has talked about those days, a little. About the Friday warm weather musical gatherings around the fountain in Washington Square and at an artist's flat when the weather turned cold, and about the fellowship of folk song bridging the wide range of fiercely held political opinions, as the music of America was passed directly from person to person in the days before folk clubs. "Tom Dooley" was part of that Washington Square heritage. There's a little discussion of those times on Billy's live album.

We can lose track of what happened in those days without someone like Billy Faier to set us straight. He was there, in the middle of it all. And not just in New York. Some particulars are handy. For instance, Billy took up the banjo in 1947. The 33 rpm long-playing record was introduced by Columbia Records in 1948. Woody Guthrie had written "This Land is Your Land" in 1940 and recorded at least two versions of it in 1944 for Moe Asch, but it was not released on record until 1951. In those years, LP recordings were on ten-inch disks, including Decca's pressing of the first Weavers LP, also in 1951. That album did not include "Goodnight Irene," by the way. By 1952, when Moses Asch and Harry Smith put together and released the landmark Anthology of American Folk Music, Billy was in San Francisco, following the music and working as a conductor on the California Street cable cars. He was given, person to person again, one of the great, neglected American folk songs by a former Alabamian named Will Calvin. It was called "The Great Assembly." It's the first song on this album, along with more of the story. At about the same time, Billy was making field recordings and sending them to Asch. Asch lost them, and our music is a little poorer for that. But Billy Faier still carries them in his memory and hands, and that's an incredibly rich gift to us all.

Back in New York City, Stinson Records decided to release a six-volume compendium of folk music entitled the American Folksay series. It's yet another one of the stories that is still being pursued around here, but the tracks appear to have been mostly recorded by Moses Asch in the 1940s. They included songs by Woody Guthrie, Cisco Houston, Huddie Ledbetter, Sonny Terry, Pete Seeger, Josh White and others, a mix of very old tunes and some written in the 1930s and 1940s by folks like Ledbetter and Guthrie. They also included four songs by members of an unnamed trio, newly recorded just before the release of the series in about 1953. The members were Roger Sprung, Erik Darling and Bob Carey, and yes, after Alan Arkin replaced Mr. Sprung (and yes, that Alan Arkin) the trio would be known as the Tarriers and make some history of their own, starting in 1956-7.

So what's all this got to do with Billy Faier and "Tom Dooley?" Well, one of those four songs was "Tom Dooley." And Billy stepped in a while back to help us find the trail of the music, by way of some background, some guidance and an introduction to Mr. Darling. It turns out that pioneering New York trio did have a name, after all. The Folksay Trio.

And that's when it gets really interesting. If you listen to Frank Proffitt sing his family's song, it's a morality lesson that could be delivered by a stern old-timer of either sex, complete with a finger pointing at the miscreant whose name is the title. But the victim is named as frequently in the lyrics as the killer, and her name was Laurie Foster. And the deed is spelled out in direct accusation, "...then you went and killed her and then you hid her clothes..." It's not a "bad man ballad" but a lesson and a memorial and a notation of the power of the law. Grayson wasn't part of any love triangle, he was the sheriff in these lyrics. The hollow where that oak hanging tree was to be found had a name--Yander's Valley. And you really should try to find the recordings of Proffitt. He has one of the most eloquent, clear and compelling voices in all of our music, reminiscent of another favorite around here, Cisco Houston. The point here, however, is that if you take the name of the victim and the details of the deed out of the song, set the events into a triangular relationship and move the verse about Grayson up closer to the front, you pretty much change the whole thing.

If you keep digging you will find the song has laid open an entire vein of history in the years after the Civil War that you might never have found without it. There are any number of details that show other sides of the story and the times, information about local pronunciation of some words ending in "a," more about Grayson and his role, and other versions of the song itself, including one recorded in 1929 at another historical cusp by, oddly enough, Grayson and Whittier. But you will find yourself circling back to those pared-down and eloquent Proffitt verses.

The meaning of the Proffitt family's song, the message, and the lyrics had gotten changed as it made its way from Carolina to New York and on to California. For one thing, there's something eerily tragic in the fact that Laurie Foster got lost. It's been pretty well pinned down that Dave Guard listened to those Folksay disks. Two of the four songs from the Folksay Trio, "Tom Dooley" and "Bay of Mexico" found their way onto the Kingston Trio's first album. And that distinctive pause in the lyrics of the popular recording, between "Tom" and "Dooley," was introduced by Sprung, Darling and Carey in their 1953 version and reprised by the Tarriers on their initial album in 1957. That was a year before the Kingston Trio's track, complete with that same pause, was buried in the middle of the first side of their June, 1958 debut album.

None of that is meant to be a veiled knock on the Kingston Trio. A lot of folks would never have been moved to find the musical traditions, artists and history that formed the foundation for the Folk Explosion started by Guard, Nick Reynolds and Bob Shane (ok, restarted if you're going to advance the Weavers again), and then got somehow submerged. We've met Reynolds and Shane and Guard's replacement, John Stewart and they have proven to be likable gentlemen and encouraging of efforts to tell the whole story of the music. They love the music. So do we. That gives us a lot to talk about...

Instead, that's all by way of noting that "Tom Dooley" and a lot of other songs played roles in the older America and its communities well beyond those related to entertainment. There's also a sort of purity, along with hard-knuckled innocence and a healthy dose of tempered bawdiness, among other things in those songs. Some of that got obscured by the commercial demand for big harmonies and ringing instrumental arrangements during the period that Ramblin' Jack has called "The Great Folk Scare" of the late fifties and sixties. And a lot of it is still worth tracking down, now.

You won't be alone in the search. All these years down the road, people are starting from those "Folk Scare" albums and going mining again for truths from before, and for the artists who might have been lost forever if not for the "Scare." Look who turned up during its height to play for those big audiences: John Hurt, Dock Boggs, Elizabeth Cotten, Clarence "Tom" Ashley, Skip James and all the others found by the likes of Ralph Rinzler and Mike Seeger and others. But don't forget that many of their names were known from, and the clues to their whereabouts found in, Harry Smith's Anthology of American Folk Music, brought to reality by Moses Asch in 1952.

And remember who was there, as player and witness, from the Forties to the Tens of a new century-- Billy Faier. Telling the truth, writing of his times, polishing his skills and preserving the stories and lessons of American folk music. And talking on the telephone to his friend, Frank Proffitt from time to time...

He has not wavered in his love of our people's music, and the media of its discovery and dissemination in the times before it became suddenly commercial. He continues to challenge us to consider that record of our inheritance and the things it tells us about ourselves and the nation. He'll tell you flat out that he believes the commercialization of the music in the fifties and sixties set true American folk music back by years, if not decades, and threatened the loss of the beauty and meaning of our folk songs, our common heritage, from a cultural point of view.

And once he has your attention, he'll invite you to consider the wonder of the way the music wove its magic and spread our lore--voice to voice and place to place--in the times before mass media paid heed. You find yourself later considering questions that would not have awakened before. Like what might be different if those musical pathways had remained threaded all the way down through the culture, there for the finding, rather than commercialized? How would we be different and who would we be? What we do owe musically to our new generations and those to be born, here on this old land? What songs do we teach them? And it's about then that you really begin to appreciate what he has given you, and the care with which he wrapped it.

If any of that moves you to go looking for that Frank Proffitt album on Folk Legacy, check out the song that appears six before "Tom Dooley." It's called "Cluck Old Hen." It's also the third song on the new live album by Billy Faier. It's been around a long time, and the folk process yielded an array of treatments, spun around a common core. Billy's interpretation springs from a version heard back at the dawn of vinyl, as reissues of 78 rpm shellac on a pair of 10-inch Decca 33s. They were called Listen to Our Story and Mountain Frolic, and if they ever saw a radio turntable it would surprise the heck out of us. Billy carried the song forward, and if you can listen to him perform it without your toe tapping, well...

If any of it moves you to go looking for Billy's albums, they're right below.

And, remember those Yellow-Billed Cuckoos? The rain crows? Some say they sing a particular song before hard rain's arrival. They summer in America and winter in South America, and all that relates directly to two more of the songs on this new live album. Two of the ones written by our friend...

Billy Faier is nothing less than an American treasure. If you listen to him in performance, you will be especially taken by the depth of his art, the sharing of wisdom and humanity, and the shading and coloration (and sometimes, punctuation) from those stunningly agile hands. The samples above will have given you a hint of what we're talking about.

You have to wonder what would happen if we went looking for the neglected artists from our musical past now, fifty years after John Hurt turned up herding cattle in Avalon, Mississippi, right where he'd been all along? He made those incredible sounds on his guitar without ever using fingerpicks. Billy Faier does the same thing on banjo...

(A note about the Limited First Edition)

There are some serious gaps in the artists and recordings available on compact disk. A number of labels are doing a great job of re-issuing recordings, but the gaps remain, and some are simply too important to ignore or accept.

Sometimes the reason for the missing material relates to questions about the commercial viability of a re-issue, and sometimes it has to do with other questions about the market for particular recordings, particularly in very small production runs.

So we decided to look for a way to fill some of the gaps.

This release from the Northern Plains Archive is initially offered as a First Edition limited to 150 copies. Each is numbered. Each is handmade. The inserts are printed on-site and trimmed with an X-acto knife whose whereabouts is often the subject of discussion. The recordings are cut to compact disk media printed here, one at a time. They are marketed directly to the public, making a much larger share of proceeds available to the artist. And copyrights are registered, wherever practical, not just in our name, but also that of the artist.

If the public decides that a release demands more than 150 copies, so be it. We'll make the arrangements for more normal production and distribution of a second edition. But there won't be any more of the Limited First Edition.

We think they're special. We hope you agree.

Now it's time to go look for the X-acto

blade. Again.

(Image is from the insert to the compact disk.)

|

Click

here to visit or return to the 1950s-60s American Basics Collection Shelves. |

|

|

Click

here to visit or return to the Complete American Basics Collection Shelves. |

Billy Faier's Historic Recordings

The

Art of the Five String Banjo

The

Art of the Five String Banjo

Original release on Riverside Records

Billy

Faier--Travelin' Man

Billy

Faier--Travelin' Man

Original release on Riverside Records

The Beast of Billy Faier

Original release on Faier Records

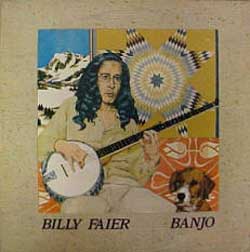

Billy

Faier--Banjo

Billy

Faier--Banjo

Original release on Tacoma Records

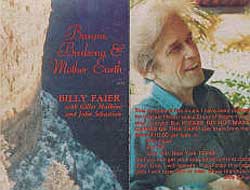

Banjos,

Birdsong and Mother Earth

Banjos,

Birdsong and Mother Earth

Original cassette release on Faier Recordings

To purchase these recordings, visit www.billyfaier.com